Footnotes

| ↑1 | Bersch, A.-K., & Osswald, L. (2021). An alle gedacht?! Frauen, Gender, Mobilität - Wie kommen wir aus der Debatte in die Umsetzung? Discussion Paper. TU Berlin. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Best,H., & Lanzendorf, M. (2005). Division of labour and gender differences in metropolitan car use: An empirical study in Cologne, Germany. Journal of Transport Geography 13, No. 2:109-121. |

| ↑3 | Kawgan-Kagan, I., & Popp, M. (2018). Sustainability and Gender: A mixed-method analysis of urban women's mode choice with particular consideration of e-carsharing. Transportation Research Procedia 31:146-159. |

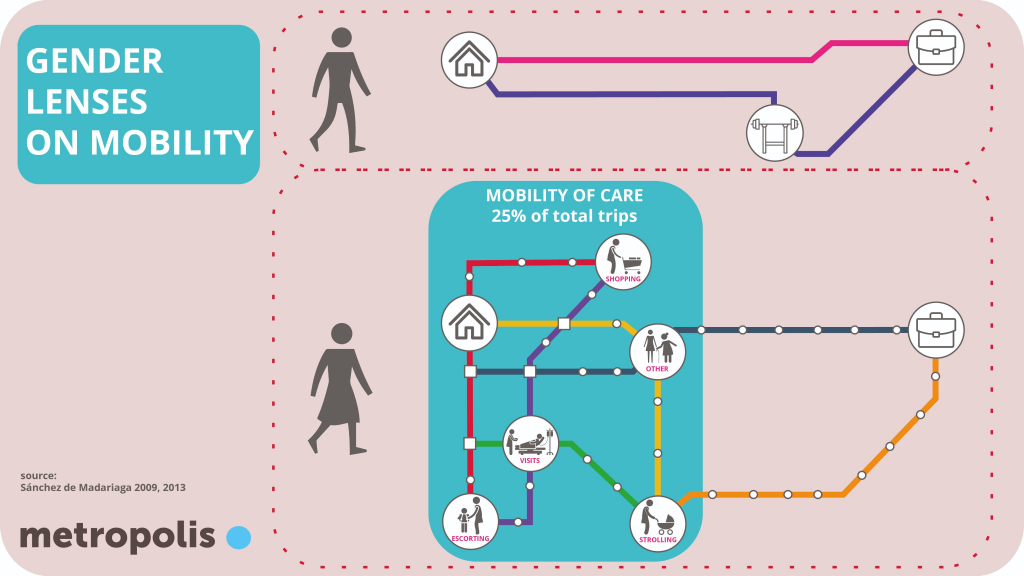

| ↑4 | Nobis, C., & Lenz, B. (2005). Gender Differences in Travel Patterns. Role of Employment Status and Household Structure. In Transportation Research Boards (Eds.), Research on Women's Issues in Transportation. Report of a conference (p. 114-127). Washington, D.C.: TRB. |

| ↑5 | Ypma, L. et al. (2021). Female Mobility. https://www.womeninmobility.org/femalemobility [06.06.2021]. |

| ↑6 | Kawgan-Kagan, I. (2015). Early adopters of carsharing with and without BEVs with respect to gender preferences. European Transport Research Review 7, No. 33. |

| ↑7 | Canzler, W. (1996). Das Zauberlehrlings-Syndrom. Entstehung und Stabilität des Automobil-Leitbildes. Ed. Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung. Berlin:sigma. |

| ↑8, ↑13 | Brandt, U., & Wissen, M. (2017). Imperiale Lebensweise. München:oekem. |

| ↑9 | Butler, J. (1991). Das Unbehagen der Geschlechter. Gender Studies Edition. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. |

| ↑10 | Meißmer, C. (2018). Gleichstellungsindex 2018. Gleichstellung von Frauen und Männern in den obersten Bundesbehörden. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Staat/Oeffentlicher-Dienst/Publikationen/Downloads-Oeffentlicher-Dienst/gleichstellungsindex-5799901187004.pdf;jsessionid=C9E9FBF6D8E9FB582DB32805D644918B.internet8732?__blob=publicationFile [06.06.2021]. |

| ↑11 | https://www.dabonline.de/2019/07/09/architekten-kammer-statistik-2018/ [06.06.2021]. |

| ↑12 | Kemfert, C., & Egerer, O. (2017). Frauen sind in Top-Positionen der größten Energie- und Verkehrsunternehmen in Deutschladn deutlich unterrepräsentiert. DIW Wochenbericht Nr. 47. https://www.diw.de/documents/publikationen/73/diw_01.c.570200.de/17-47-4.pdf [06.06.2021]. |

| ↑14 | https://www.dena.de/newsroom/meldungen/verkehrswende-umfrage-verbraucher-offen-fuer-politische-massnahmen-im-verkehrssektor [06.06.2021]. |